Hi Ally,

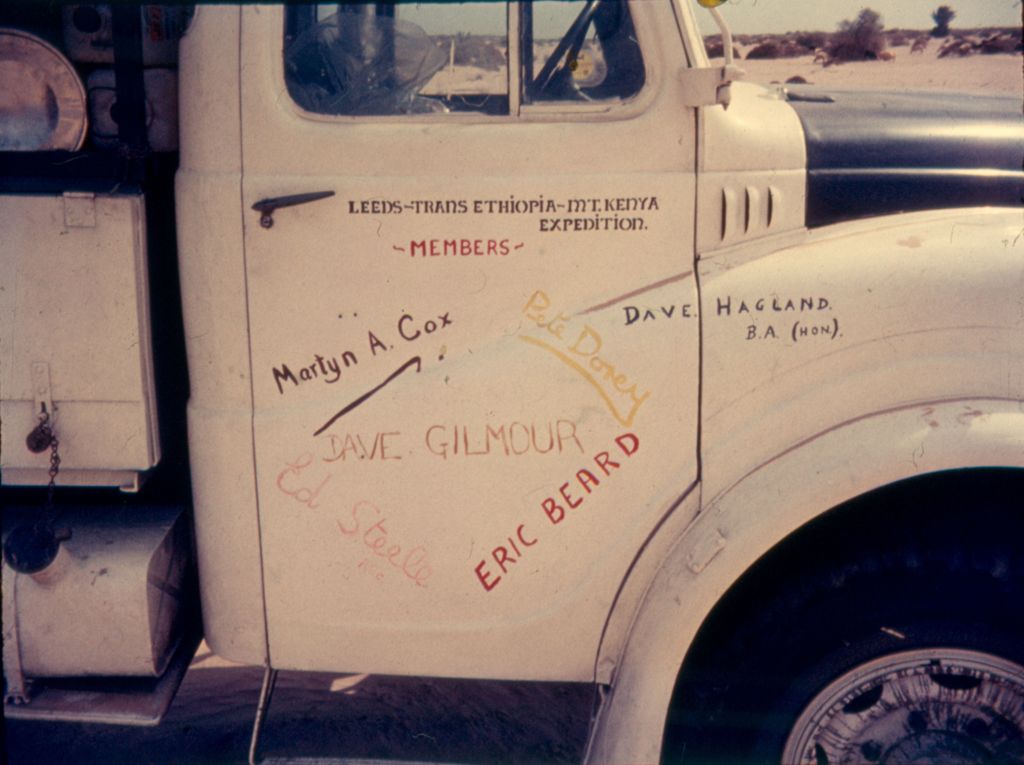

I organized an expedition to drive from Leeds, across North Africa, south through coastal Sudan and then transit Ethiopia. The goal was to climb Mount Kenya and Eric Beard joined us as a member of the climbing team. We left Leeds at the beginning of July 1969 and got stuck, as did several other expeditions, at Giza, Egypt – casualties of the Arab / Israeli war. Eric was a great team member and I have fond memories of him fixing tea for everyone an hour earlier than our intended departure and then heading off down the desert highway, running ahead of our expedition truck. The goal of the Expedition was abandoned in Egypt and we independently made it back to England in early September. It was many years later before I learned from Eric’s close friend, Dave Gilmour, that Eric had been killed in the M6 auto accident, just a few weeks after our return from Africa.

A great loss of a good mate,

Ed Steele

–

Thanks so much for getting in touch Ed.

I may make a follow up post to the piece I wrote on Beardie. Nothing special, just a lazy cut and paste job of some of the stories people have sent me about him. It would be a shame just to leave them festering in my inbox. Knowing the time it takes me to get these things done I’ll likely get round to making a start sometime in the next decade or so, would you mind if I included what you sent me here?

Many thanks, Ally

–

That email exchange is from 2018. I may be tardy but at least I’m self aware.

Ed went one better than what he’d already written, sending me a full chapter about the expedition from his book Ego Trip. Why this came to mind today of all days I have no idea, though coincidentally it is the 53rd anniversary of Beardie’s death.

Chapter 5 – The Leeds-Trans Ethiopia-Mount Kenya Expedition

The expedition truck was a military surplus Austin K-9 four-wheel drive, and was equipped with such useful features as a machine-gun turret and cab-roof lighting. I had installed the latter in the form of two additional 75-watt sealed beam headlamps that were almost 9 feet above street level. The assumption was that these lights would provide illumination for cross-country nighttime driving, rather like the “Baja” equipped race vehicles. In fact the scattered glare from these lights made them unusable in dust or fog conditions, although they were really good for intimidating both oncoming drivers and security checkpoint guards. The machine-gun turret was also a useful feature. The truck was designed to carry both troops and general cargo, and had an open back with a tarpaulin over a tubular frame to protect the load. The original tarpaulin was torn and rather than repair this, we chose to buy another used military tarpaulin. The tarp we purchased was from a much bigger truck, so it was necessary to double it to fit over the original torn tarp that we left in place. Naturally the tie-downs did not fit but we solved this by lashing the “new” tarp with an old rock-climbing rope, criss-crossed back and forth every couple of feet. The result was a triple-layer tarp that provided good thermal insulation, plus a network of climbing rope across the roof of the bed. This enabled a reasonably limber passenger to climb out of the back of the truck, across the roof and then into the cab through the machine-gun turret–all while the truck was in motion!

The bed of the truck had benches down each side for the troops to sit on; they now doubled as lockers for our spare parts and expedition supplies. We had equipped the truck with two hammocks that were slung lengthwise above the side benches. The balance of the stores was dumped into the well between the benches, leaving the latter clear for sleepers. The truck could therefore sleep four persons in the back during transit, while a driver and passenger occupied the forward cab (of course, the passenger’s job was to both navigate and keep the driver awake). The Austin K-9 was a favorite amongst university expeditions: it was larger than a LWB Land Rover, and because it was typically purchased as military surplus, it was also much cheaper. The four-liter engine turned out 90 BHP at 3000 RPM and provided a surprisingly good fuel consumption of 12 miles per gallon versus the 14 mpg of the Land Rover. (For you techno-geeks, note that all quoted gallons are “Imperial” gallons not US gallons.) The truck was fitted with two 25-gallon fuel tanks in addition to the standard 20-gallon main tank. One tank was mounted high behind the cab and gravity fed the main tank with a simple push-pull shutoff. The other was bed-mounted opposite the main tank and fed into the main tank via an auxiliary electric pump. I mention these because they had never been filled with gasoline before we left Leeds. The side tank was known to be “clean” as we had repaired a leak where the original drain plug had been sheared off. We had, however, never checked the “behind the cab” gravity tank.

The Expedition Begins

The day finally arrived when we were to begin the expedition. We filled up all three fuel tanks and on July 2, 1969 we set off south, driving towards the Dover ferryboat. The scrap of paper I have that survives as my log shows that the odometer read 45,775 miles upon our departure. We made an overnight stop in Birmingham and headed off again the following day.

When the main tank was low on fuel, the passenger would lean out the window to open the valve on the gravity tank, until the fuel gauge showed that the main tank had been refilled. The first mechanical problem showed itself when the engine spluttered and died and we coasted to a halt on the freeway. I immediately diagnosed the problem as fuel starvation and found that the fuel pump was outputting no gasoline. We had three spare pumps and within minutes, the spare was bolted on and we were on our way again. Dave was driving (all of the bad things happened while Dave was driving!?) and I sat in the back, cleaning the clogging sediment out of the original fuel pump. Dave Gilmour and I were the only licensed drivers and our plan was that by alternating drivers, we could drive non-stop until we reached Nairobi. The fuel starvation problem was repeated again in France on July 5th in the Foret de St. Germain, but after that the tank sediment had been pretty much flushed out of the system.

The remainder of the drive across France was uneventful and we began to cross the Alps bound for Italy. After a long upward climb, we halted the truck in order to allow the engine to cool and took the opportunity to brew tea at the roadside. Eric Beard, an ultra-marathoner, took off running (in the direction we were going I might add). When we caught up with him, he just climbed aboard. This pattern was to be repeated over the next couple of months: each morning Eric would wake first and often fix tea for everyone. He would then take off running and after we broke camp and left, we would catch up with him, many miles down the road.

The truck did not have a particularly good turning circle and on one hairpin bend, the turn was too tight to make. Dave, who was driving, threw the truck into reverse in order to continue the turn. In the back of the truck, we watched in horror as a small Fiat disappeared under the rear of the truck. Between the Fiat’s honking and our yelling, we caught Dave’s attention, whereupon he stopped and then drove forwards. The Fiat had a fabric sunroof which was now torn. The driver examined the damage, swore at us in Italian and then tore off down the highway. Whew!

Besides having a wide turning radius, the truck was also physically quite wide. In one Italian town we followed signs to a camping area and found ourselves on a narrow one-way street, with parked vehicles on both sides of the road. There was one vehicle that was parked such that it protruded just a little too far into the street, and we could not squeeze by. Dave used a knife to open the side window and we unlocked the driver’s door. We then released the brake and pushed the offending vehicle down the road, until we were able to turn it into a side road and re-park it, locking the door again as we left. The owner is probably still looking for it but the long line of jammed traffic behind us made no objection as they sat there calmly blowing their horns.

In Palermo we camped near the beach as we waited for the Palermo-to-Tunis ferryboat. We swam in the warm Mediterranean Sea and relaxed after the long drive. The camping arrangements were such that some of the lads slept in the truck and a couple simply bivouacked beside the vehicle. On one evening the mosquitoes found me and I decamped to the cab of the truck, which became my preferred roosting spot for the remainder of the trip. The cab was wide enough that I could stretch out fully across the padded seats and had the added advantage that I could lock the doors: if a machete-wielding mob attacked the expedition, I could fire up the engine and drive off to the nearest consulate in complete safety.

While awaiting the ferry, Dave, Eric and I also took the opportunity to climb the nearby sea-cliffs. This was the first time we had climbed together and we imagined that our route was probably a “first ascent.”

July 9, 1969 – Africa!

We landed at Tunis after driving 2,120 miles from Leeds. This was one week after we had left Leeds, and included three sea crossings by ferryboat. After a brief visit to the ancient Roman ruin of Carthage, we began the next driving leg to the Libyan border, arriving on the evening of July 10. At the border we came across two fellow expeditioners in a VW. They had a flat tire and were out of fuel. We gave them some fuel, as we had plenty, and used the Austin’s built-in air compressor to inflate their tire. They were impressed.

I do not recall too many problems with border guards or other officialdom, although there were a couple of incidents that were due to our ignorance of local customs. One day as we headed along the North African coast road towards Egypt, a police officer flagged us to halt, or so we thought. I was driving at the time and stopped to see what the problem was. He climbed into the cab and motioned me to proceed. Off I drove. There were several places in the road where a bridge was missing and there was a gap in the pavement. Here tire tracks in the sand showed that we were supposed to drive off the road, across the sandy wadi and up the bank on the opposite side to regain the pavement. There was usually a faded sign indicating a speed limit of 15 kilometers per hour at these diversions. With our big, tough truck, we pretty much ignored the limit signs and roared down into the wadis and back up onto the highway again. The policeman gasped a few times, turned a little pale but said nothing. After an hour or so he signaled for us to stop. When I did, he explained in sign language that I was to drive slower in future and then he let himself out of the cab before heading off across the desert on foot, to some unknown destination. Now we knew how someone waved for a ride when hitchhiking in Africa.

The coastal road was just wider than a single vehicle; the custom was to drop one wheel off the road onto the sand when passing oncoming traffic. There were frequent military convoys and apparently it was the also the custom that military vehicles had priority. When such convoys approached, civilians had to drive completely off the pavement. Since we did not know this and since we were also driving a large military type vehicle, we adopted the egalitarian approach and only gave up half a lane. This created some close shaves, as we forced oncoming convoys to play the game properly.

Night driving was also a strange affair. The Arab drivers had no understanding of full beams versus dipped beams. Some just drove on main lights, with no attempt to dim their beams. Others adopted a strange custom where one car has its main beams on and the oncoming car turns its lights off completely; at some point they would alternate lights on, lights off. We were puzzled and would give a quick, “polite” flash of the main beams, to indicate to the oncoming driver that they should dim theirs, as our lights were also dimmed. When this had no effect, we threw the switches for our roof headlamps. Nothing would happen until we hit our “flash” button on the dash. When this occurred, all four 75 watt sealed headlamp beams would light up and night would become day as the paint began to blister on the front of the approaching vehicle. Ah, the joy of seeing the other drivers, arm thrown across their faces, attempting to shield their eyes as they drove completely off the road, dazzled and blinded. Such simple pleasures!

Again we “team drove” along the coast road and arrived in Benghazi on the morning of July 14. We met an English expatriate couple who offered the front yard of their villa as an overnight campsite. My fondest memory of Benghazi is the smell of honeysuckle and jasmine bushes on a warm evening. The following day we camped near the Roman ruins of Cirene, a beautiful and lonely site. The reconstructed temple sits near the seashore and looks out over the Mediterranean. We reached the town of Tobruk on the evening of July 16. Here we took a break and made a detour to visit the nearby British military base at El Adem. The recapture of Tobruk on 11/13/1942 ended the battle of El Alamein, when British General Mongomery decisively defeated German General Rommel. That was the turning point of WW II for Britain. Churchill later commented that before El Alamein, the British had not won a single battle, and after El Alamein, they never lost one.

The remains of WW II were scattered all around us. The El Adem base had an interesting museum of WW II artifacts, particularly the land mines deployed by all combatants. The British army still used the area around El Adem to train troops in desert warfare. They warned us to be extremely careful when driving off the highway, for example when looking for a place to camp for the night; there remained extensive uncleared minefields dating back to the war, and the coast road had only been cleared of the mines for some 15 feet to either side of the pavement.The base also had a military store where we were able to purchase a quantity of duty-free booze (not for consumption of course but for trade along the way). Eric took the opportunity to use the base athletic track to do some running. The soldiers were stunned to watch Eric making circuit after circuit of the track in the heat of the day.

Egypt

Reluctantly we abandoned the hospitality of El Adem and set off again on the morning of July 18, reaching the Egyptian border the following morning. This crossing was a little more complicated than previous border crossings, as this was 1969 and Egypt was still at war with the State of Israel. Six likely lads in a military style truck were regarded with more than a degree of suspicion. Nevertheless they issued us Arabic license plates for our truck and passed us through the checkpoint to drive to Alexandria, although we were warned it might not be possible to proceed to Cairo. We set out again on the coast road where every few miles were military checkpoints. These usually consisted of a couple of soldiers with rifles and a plank laid across a couple of oil drums. We would roar up in our obviously military truck, the soldiers would scurry to lift the plank and we would coast through the checkpoint, waving cheerfully as we went by. The soldiers would gape at us but they had no telephones or radios and they did not open fire.

The evening of July 19 we arrived in the resort town of Marsa Matruh and camped on the beach. There were hundreds of Egyptian youths also camping here and we soon struck up conversations with students from the University of Alexandria. They showed us a nearby cave that Rommel had used as his headquarters and we swam and lazed in the sea. Marsa Matruh was already a popular beach hangout for Egyptians but at the time we visited, there was no local fresh water source; all drinking water was trucked in. Today there are wall-to-wall, multi-story hotels all along the beachfront. When we visited, none of this existed and we sat around a campfire on the beach while our new-found Egyptian friends sang patriotic songs and danced in the firelight. When they asked where we were from, we said “Leeds.” Puzzled looks all around. When we said “Leeds United,” their faces lit up immediately. Everyone knew how well “our” soccer team had performed in the European cup. They insisted that we sing, too, and they wanted to hear “Those were the days,” the 1968 hit single by Mary Hopkins. Our singing sucked but Eric Beard had brought a guitar and his playing was a big hit.

The following morning our Egyptian friends asked for a ride to Alexandria and insisted that we stay at their home. The drive was made exciting by the fact that Alexandria has a railway and Dave, either unaware or having forgotten that we were all traveling on the roof of the truck, drove under a couple of low-clearance rail bridges. The first time this happened, I yelled at everyone to lie flat, as they were all facing the rear and unaware of their peril. I threw myself off the roof and clung to the ropes on the side of the tarpaulin as we rocketed under the bridge. Fortunately there was a foot or so clearance but there would have been tragedy if my companions had not been lying prone. We drove along narrow lanes to the home of our Marsa Matrouh friends and I was discomfited to discover that I was expected to share a bed with an Egyptian male. This did appear to be an innocent cultural difference but I nonetheless slept inside my expedition sleeping bag on top of the bed, in order to protect my chastity.

On the morning of July 21, we drove from Alexandria to Cairo. We had been told that it was illegal to stop on the highway, as the route passed through several militarily sensitive areas. We did make a stop and were brewing tea at the side of the road when two armed soldiers approached us. We offered them tea and they were very friendly. One of the soldiers offered his AK-47 automatic rifle to me to examine. When I handed it back to him, he fired several rounds into the air, to show us how well it worked. We thought this would be a good time to leave.

Cairo was an exotic and strange town. Unlike Tunis, Tripoli and Benghazi, the town positively hummed with crowds of people. Most were wearing what to us looked like long nightgowns. The few buses were rundown, smoke-belching antiques, crammed beyond comprehension with humanity, including dozens of Egyptians clinging to the exterior. There were few cars–in fact most of the vehicles were Russian -built military trucks. There were many of these broken down by the side of the road, suggesting that either maintenance or reliability was a serious problem.

We decided that we needed cash so Peter and Martin carried our duty-free booze off to the crowded suq (marketplace) to see if they could find a buyer. In the meantime, the four remaining expedition members were sitting in the truck, parked on a side street. After we had been there a few minutes, a pedestrian introduced himself as a former diplomatic translator at the United Nations. We chatted for a while and as we talked, a large crowd gathered. Ten minutes later a police car with a couple of officers joined the melee. They asked us what we were doing and we explained that our two friends had gone into the market to buy groceries and we were simply waiting for them. Now a lieutenant had joined the even bigger crowd. He insisted that we immediately follow them to the police station to be questioned. We in turn insisted that we had to wait for our two friends, as there would be no way they could possible know where we had gone. The argument continued and we were extremely relieved when Martin and Peter showed up. We followed the police car to the station and the lieutenant suggested that we pay one of the officers to guard the contents of our truck for us. We asked who was going to guard the guard and instead insisted that we leave one member of our group with the truck. This seemed to satisfy everyone and five of us trooped into the station to be “questioned.” The lieutenant asked for and took away our passports. At this, we became a little concerned and decided to send Dave Hagland on a walking trip to the British Embassy to seek assistance. The Egyptian officers did not seem to notice the loss of another of the company and we all settled down to wait. Several hours later, Dave showed up with a vice-consul from the Embassy, who began a tortuous discussion in Arabic with the Lieutenant. Two hours later, the police admitted that we probably were not Israeli spies and released us.

The now-reunited expedition motored on and camped just south of Cairo near the pyramids at Giza. We arrived here on the morning of July 22, 20 days and 4,427 miles from our beginning in Leeds. The campsite at Giza was wonderfully exotic, with the Great Pyramids and the Sphinx to decorate the scene. The campsite itself was on an otherwise barren sand plain and there were several other expeditions of different nationalities camped nearby.

The next stage of the journey required us to drive along the Nile valley to Luxor and then cut across unpaved desert roads, crossing the Eastern Arabian Desert to the Red Sea coast. We would drive along the coast to Massawa in Eritrea, before heading back into the interior via Asmara and thence to Addis Ababa. To do this we needed permission from the Egyptians to drive south. This, it seemed, was a problem. They claimed that the Israelis had raided their Red Sea coastal installations with a series of commando raids, and the route was now closed by road. We could take a train to Aswan, or we could return by train to Alexandria. We were not permitted to drive back the way we had arrived. There were several other university expeditions in the same fix as ourselves, some of which had been waiting weeks for permission to proceed. We had a couple of problems. First was that we lacked the cash to finance rail travel and second, our truck was too big for their rail cars.

We made several trips to Cairo to talk to Egyptian officialdom but they remained adamant. We did take this opportunity to visit the famous Egyptian museum. The doors were protected by sand-bagged blast walls and the windows were taped to prevent flying glass in the event of air-raids. Many of the exhibits had also been removed to safe storage. Nevertheless it was a fascinating museum and a wonderful place to visit. I visited this museum again in later years, by which time the war with Israel was a dim memory. On my second visit I was besieged by tour guides and non-stop hustling, all delightfully absent on my first visit. Back at Giza we had been hustled non-stop by Egyptians wanting us to take camel rides and the like. Two German lads we met told us the secret. When you are first approached by the touts, you look confused. They rapidly switch their sales pitch from English to French to German etc. Then you show a glimmer of understanding and you tap your chest and say, “Czecho.” The touts did not speak Czechoslovakian and further knew that the Czech road construction workers from the Soviet Union had no money. The touts would scowl and swear something in Arabic, and thereafter we were left entirely in peace, while the word spread far and wide that we were worthless as customers.

We had met the two German lads, Dieter and Gerhard, at the Giza campsite. That evening in a nearby bar, we drank beer and watched in awe as Neil Armstrong stepped onto the surface of the moon declaring, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” I had always assumed that I was watching live television at the time but in 2008, I read from the BBC archives that this event had occurred earlier that day at 0256 hours GMT on July 21, 1969.

Meanwhile our expedition was stuck. We lacked the resources to continue on a route other than the one we had planned. After some discussion we decided the following. Martin and Peter would take the train to Aswan, thence by ferry to Wadi Halfa, continuing by train to Khartoum and Massawa, followed by a boat ride to Mombasa in Kenya. Dave Gilmour and Eric Beard would sell the expedition truck back in Libya and then head off to Cyprus to do some climbing. The German lads were traveling in a VW camper and had decided to return to Tripoli in Libya. From Tripoli their planned route was south to Ghadames on the Tunisian border and thence across the Sahara using the ancient Hoggar route to Chad. I donated maps and our “sand tracks” to them to assist in their desert crossing. (Sand tracks are steel channels, designed to be laid down across soft sand so that a vehicle can be driven across without the wheels bogging) The Germans invited Dave Hagland and me to join them in their attempt and we accepted.

The problem was, how to reach Alexandria? On the trip from Alexandria to Cairo we had been told, “Daylight driving only. No stopping.” Now were told the road was completely closed to foreigners. Our solution was to drive straight through to the Egyptian / Libyan border overnight, a distance of 500 miles. The K-9 Austin took the lead, with the Volkswagen van tight behind “in convoy.” As before, the soldiers were dazzled by the lights of the truck and opened the barriers when they saw it was a military vehicle. The friendly wave as we coasted through still worked and we passed through barrier after barrier without being stopped. At dawn we approached the Egyptian border and stopped for the second time. The previous stop was an hour earlier, because Eric wanted one of the Arabic license plates as a souvenir and had removed and hidden it. The Egyptian border guards were a little surprised to see us and were upset that we did not have currency control documents. (These were to ensure that we had not changed cash on the “black market” but had instead used Egyptian banks. Naturally all of our cash was changed at the much higher black market rates.) Then the missing license plate was discovered. The officer began shouting and we explained that it had either been stolen or had fallen off. He stormed out of the office to seek guidance from superiors and I noticed that he had left our passports on his desk. I casually picked them up and walked out of the office. We climbed leisurely into our vehicles and drove the couple of hundred yards to the Libyan border. Nobody noticed our departure. Just like Moses, we were out of Egypt.